Prehistoric cave art suggests the ancient use of complex astronomy

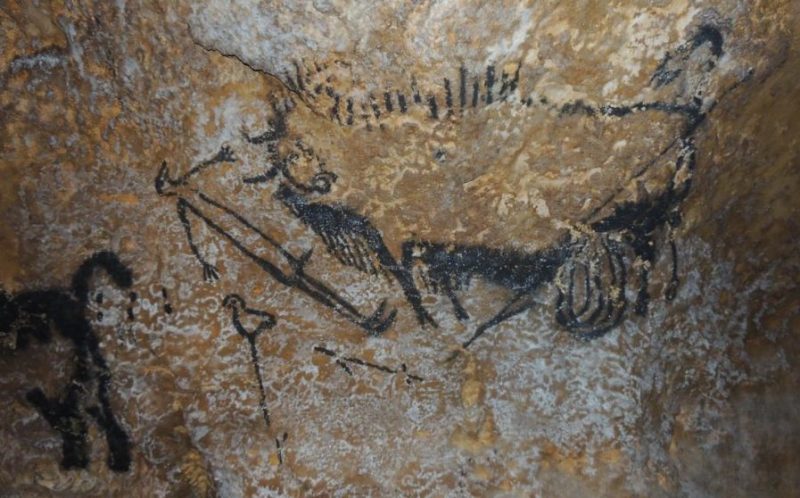

A new study says that some of the world’s oldest cave paintings reveal that ancient people had relatively advanced knowledge of astronomy. According to the new analysis, some of the paintings are not simply depictions of wild animals, as was previously thought.

Instead, the animal symbols represent star constellations in the night sky, and are used to represent dates and mark events such as comet strikes.

Researchers from the Universities of Edinburgh and Kent studied details of Paleolithic and Neolithic art featuring animal symbols at sites in Turkey, Spain, France and Germany.

They found all the sites used the same method of date-keeping based on sophisticated astronomy, even though the art was separated in time by tens of thousands of years.

The team confirmed their findings by comparing the age of many examples of cave art – known from chemically dating the paints used – with the positions of stars in ancient times as predicted by sophisticated software.

According to the study, published November 2, 2018, in the Athens Journal of History, the cave paintings suggest that, perhaps as far back as 40,000 years ago, humans kept track of time using knowledge of how the position of the stars slowly changed over thousands of years.

For example, the findings suggest that ancient people understood an effect caused by the gradual shift of Earth’s rotational axis.

Discovery of this phenomenon, called precession of the equinoxes – motion of the equinoxes along the ecliptic (the plane of Earth’s orbit) – was previously credited to the ancient Greeks.

The findings indicate that the astronomical insights of ancient people were far greater than previously believed. Their knowledge may have aided navigation of the open seas, the researchers say, with implications for our understanding of prehistoric human migration.

Martin Sweatman, of the University of Edinburgh’s School of Engineering, led the study, Sweatman said in a statement:

Early cave art shows that people had advanced knowledge of the night sky within the last ice age. Intellectually, they were hardly any different to us today.

The researchers reinterpreted earlier findings from a study of stone carvings at one of these sites – Göbekli Tepe in modern-day Turkey – which is interpreted as a memorial to a devastating comet strike around 11,000 B.C. This strike was thought to have initiated a mini ice-age known as the Younger Dryas period.