Europe’s Oldest Mosque May Be Buried Underground in This Visigothic City in Spain

Reccopolis, a rural area outside of Madrid, has witnessed an extraordinary archaeological effort, with researchers arriving at an important finding using a geomagnetic instrument that helped map walls and other structures still buried underground.

The ancient, 1,400-year-old city was found to have housed much more than the ruins currently visible at the site would imply: the yet unexplored plots of land include hidden parts of a city palace and what may be one of the oldest mosques in Europe.

Archaeologists have detected long-hidden features of a Visigothic city in Spain, including unexplored parts of a palace and a building that may be one of the oldest mosques in Europe.

Without digging, the researchers used a geomagnetic instrument to reveal walls and other structures still buried underground at Reccopolis, which is in a rural area outside of Madrid. They found that the 1,400-year-old city was far more extensive than the ruins visible at the site today would suggest.

“In every space that we were able to survey, we found buildings and streets and passages,” study co-author Michael McCormick, a medieval historian and archaeologist at Harvard University, told Live Science.

The Visigoths were Germanic people who established a kingdom in southwestern Europe in Late Antiquity, just before the Middle Ages began. They famously sacked Rome in the year 410.

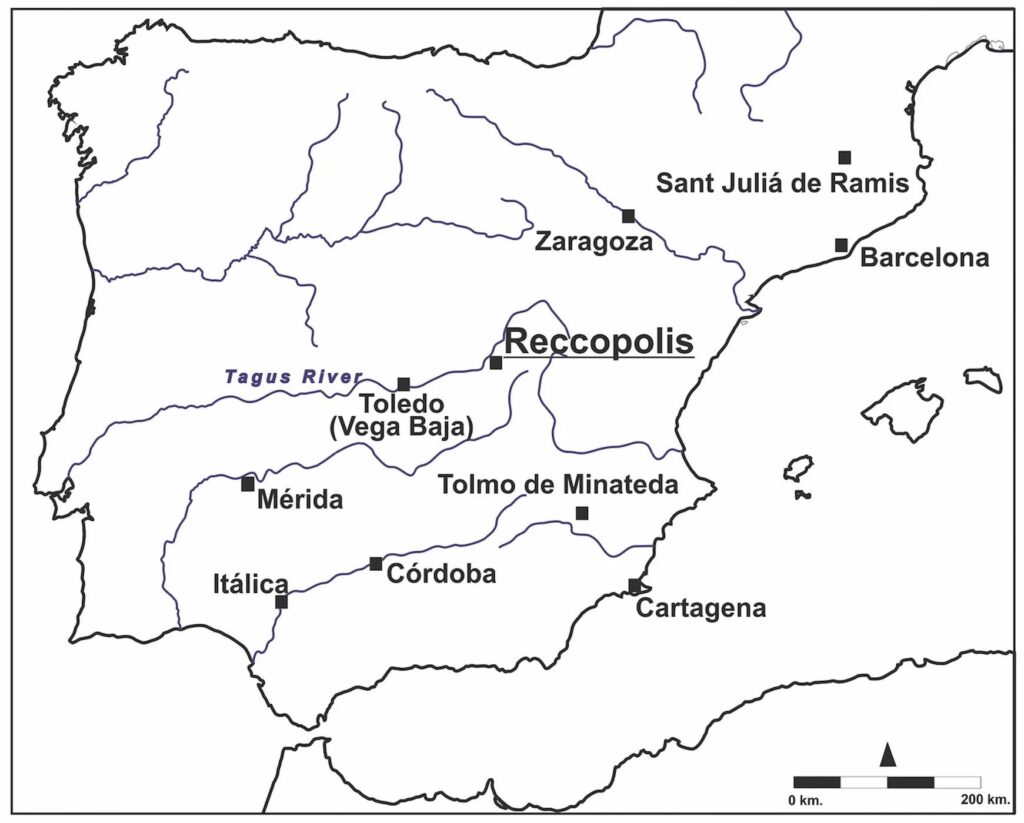

In the second half of the sixth century, the Iberian Peninsula was the centre of Visigothic power. King Leovigild made his royal capital in Toledo, Spain, and farther upstream along the Tagus River, he constructed a new town called Reccopolis in 578.

Excavations have been ongoing at Reccopolis for a few decades, but so far, archaeologists have uncovered only about 8% of the area inside the city walls.

When McCormick visited the site in 2014, he saw the remains of the palace, a chapel, and some shops. But he teased his friend, study co-researcher and excavation director Lauro Olmo Enciso of the University of Alcalá in Spain, asking, “Where’s the rest of the city?”

The researchers and a few other colleagues teamed up the next year to perform the first geomagnetic survey of the site. This noninvasive prospecting technique allows researchers to see structures underground by mapping magnetic anomalies beneath the Earth’s surface.

Their results quickly showed that empty spaces inside the city walls of Reccopolis were full of hidden streets and buildings. There was even a suburb outside the city’s monumental gate. The findings were published last week in the journal Antiquity.

“Thanks to this new geomagnetic survey, we have learned that the space encircled by the city’s walls was fully developed and that its population was large enough even to spill beyond the city’s walls,” said Noel Lenski, a professor of classics and history at Yale University, who wasn’t involved in the study. “Just as importantly, this was happening in a period long thought to be characterized by urban decline and demographic collapse.”

Reccopolis was indeed constructed amid the turbulence of the sixth century. From Western Europe to China, the era is associated with mass migrations, imperial collapse, food shortages, and famine, as well as the first known outbreak of the bubonic plague.

Researchers have recently defined a period of rapid climate change, called the Late Antique Little Ice Age — which lasted from 536 to about 660 and was brought on by a series of volcanic eruptions in the Northern Hemisphere — that may have been the catalyst for the widespread upheaval.

“It’s really remarkable to see the Visigothic monarchy coming together at this time and assembling the resources to be able to found a new city,” McCormick said.

The Visigothic rulers of the region were deposed during the Islamic conquest of 711, and the new geophysical evidence shows some signs of Muslim occupation before the city was abandoned around 800.

The researchers found one large building with a different orientation from all the other buildings on the site, toward Mecca.

The floor plan also resembles that of mosques in the Middle East. McCormick says only excavations will be able to confirm that the building is indeed a mosque. But if it is, it could possibly be the oldest remaining mosque in Europe.