A glimpse of Bronze Age girl’s daily life from hair, clothes

One of the most significant finds of the Bronze Age, the remains of a teenage girl discovered in Denmark, is starting to give up her secrets. Found in a large burial mound back in 1921, she was named the Egtved girl for the town in Denmark where she was laid to rest 3,400 years ago. Her bones had disintegrated but her clothing, fingernails and hair were intact.

That has proved enough for scientists in Denmark to start piecing together the final few years of her life.

Using strontium isotope analysis of enamel from the girl’s molar, scientists believed she most likely hailed from southern Germany. And by doing the same analysis on her thumbnail and 23-centimetre-long hair, they believe she was quite the frequent traveller in her final two years.

“The most surprising and important thing is that our strontium isotope results show that this iconic Bronze Age female find, who has until now been considered to be local and nearly synonymous (with the) Danish Bronze Age, has shown to be from abroad and seems not to have spent much time in present-day Denmark at all,” Karin Margarita Frei, a senior researcher at the National Museum of Denmark and the University of Copenhagen who led the analysis, told CBS News.

“Moreover, the strontium isotopic signatures in her hair and fingernail show that she moved vast distances several hundreds of miles forth and back probably between present-day Denmark and southern Germany,” she said. “This is the first time ever that we have been able to identify such a level of high-resolution mobility in a prehistoric individual.”

Strontium is an element that exists in the earth’s crust, and its prevalence is subject to geological variation. Humans, animals, and plants absorb strontium through water and food. By measuring the strontium isotopic signatures in archaeological remains, researchers in the past decade or so have been able to determine where humans and animals lived, and where plants grew.

The researchers from the National Museum of Denmark and the University of Copenhagen, whose findings were described Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports, believe the cremated remains of a 6-year-old girl found with the Egtved Girl also came from southern Germany. The coffin dates the burial to a summer day in the year 1,370 BC.

On its own, the Egtved girl’s strontium isotope signature made it hard to pin down her birthplace – it could indicate that she came from Sweden, Norway or Western or Southern Europe. She could also have come from the island Bornholm in the Baltic Sea. But when Frei combined that analysis with that of her clothing, it was easier to pinpoint the place of origin.

“The wool that her clothing was made from did not come from Denmark and the strontium isotope values vary greatly from wool thread to wool thread,” she said. “This proves that the wool was made from sheep that either grazed in different geographical areas or that they grazed in one vast area with very complex geology, and Black Forest’s bedrock is characterized by a similarly heterogeneous strontium isotopic range.”

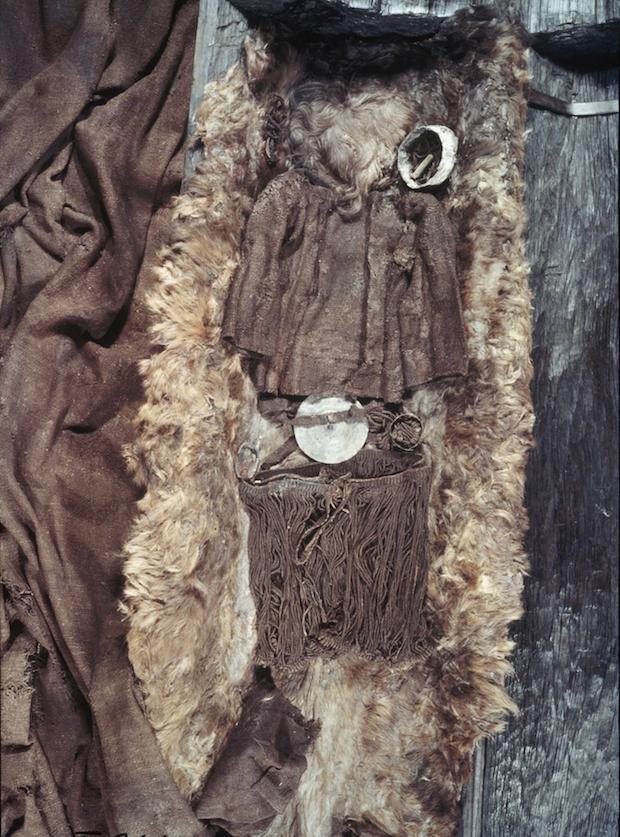

The extremely well-preserved costume of the Egtved girl consists of a short, corded wool skirt, blouse and a disc-shaped bronze belt plate symbolizing the sun, which researchers interpreted as suggesting she was a priestess of a Nordic sun-worshipping cult. She was believed to have been 16 to 18 years old. It is unknown how she died.

“She was from the elite,” Frei said of her place in society. “She is buried in an elite grave mound with the oak coffin and her outfit seems to point that she was some kind of Sun priestesses.”

Because Denmark and southern Germany were the “dominant centres of power” at the time, according to Kristian Kristiansen, one of the co-authors, the girl was likely married in a strategic power alliance to a chieftain in Denmark.

“We find many direct connections between the two in the archaeological evidence, and my guess is that the Egtved girl was a Southern German girl who was given in marriage to a man in Jutland so as to forge an alliance between two powerful families,” Kristiansen said, adding that Denmark during that time traded amber for bronze. Amber, consider equal to gold, was transported via middlemen in Germany, to the Mediterranean.

“Amber was the engine of Bronze Age economy, and in order to keep the trade routes going, powerful families would forge alliances by giving their daughters in marriage to each other and letting their sons be raised by each other as a kind of security,” Kristiansen said.

By revealing details of the Egtved girl’s life, Frei and her colleagues believe it could help scientists better understand the Bronze Age. “Now we know that people could move very fast and seem to have travelled quite a bit during their lives, so it was without a doubt a highly dynamic society,” she said.

Helle Vandkilde, an expert in the Bronze Age at Aarhus University in Denmark who was not part of the study, said the analysis was especially helpful in offering details on the travel patterns of the period.

“The new study and its cutting-edge methods are exciting and very novel because it reveals the travelling biography of one single female individual belonging to the upper social rung of society in Early Bronze Age of Southern Scandinavia,” she said. “The long distances involved, the gender and the frequency of travel are new, but should perhaps not surprising as the Bronze Age (2000-750 BCE) represented the largest known pre-modern globalization glued together by the material of bronze.”

It also shows the potential of the latest scientific techniques to give us greater insight into events that happened centuries ago. The most famous case of late has been Richard III, who died tragically after a short reign that ended in 1485. Through DNA analysis, researchers have been able to determine how he died, that he had back trouble and even his appearance – down to the colour of his hair and eyes.

In a similar case, researchers used whole-genome capture to retrieve the DNA from the 400-year-old skeletal remains of three slaves, known as the Zoutsteeg Three. They were able to determine that the slaves came from Bantu-speaking groups in northern Cameroon and non-Bantu-speaking communities living in present-day Nigeria and Ghana.