A Crucified King and Mysterious Bones: Whose Remains Were Hidden in the Abba Cave?

The Abba Cave is best known for being a tomb that contained the remains of a person who is believed to have been crucified. This cave is located in Givat HaMivtar, a suburban neighbourhood in the northern part of Jerusalem.

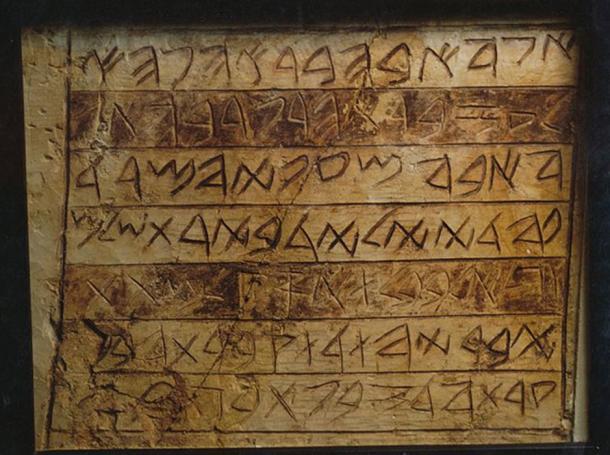

The cave derives its name from the Aramaic inscription found on the wall of this tomb. According to this inscription, the owner of the cave was a man by the name of Abba, who was the son of the priest Eleazar, and the grandson of the high priest Aaron. Many questions surrounding the Abba Cave have yet to be satisfactorily answered.

Discovering the Cave

The Abba Cave was discovered in 1970/71, when construction workers who were building a private home stumbled upon it by accident. When the cave was explored, it was discovered that it had two chambers. In addition, an ornately decorated ossuary was found. These were limestone boxes that were used for the secondary burial of bones.

The Abba Cave has been dated to the 1st century BC, and during that time, the customary practice was to collect the bones of the deceased after the body had been buried for almost a year and have them reinterred in an ossuary.

The identification of the ossuary’s owner was determined based on the Aramaic inscription on the wall of the cave. As mentioned earlier, the inscription mentions that the cave belonged to a man by the name of Abba, whose father and grandfather were Eleazar (a priest) and Aaron (a high priest) respectively.

In the inscription, Abba describes himself as “the oppressed” and “the persecuted”. Born in Jerusalem, Abba was exiled to Babylon. When he returned to the city of his birth, Abba brought back a man (or perhaps his remains) by the name of Mattathiah, the son of Judah, and “buried him in the cave that I purchased”, i.e. the Abba Cave.

Who was Mattathiah?

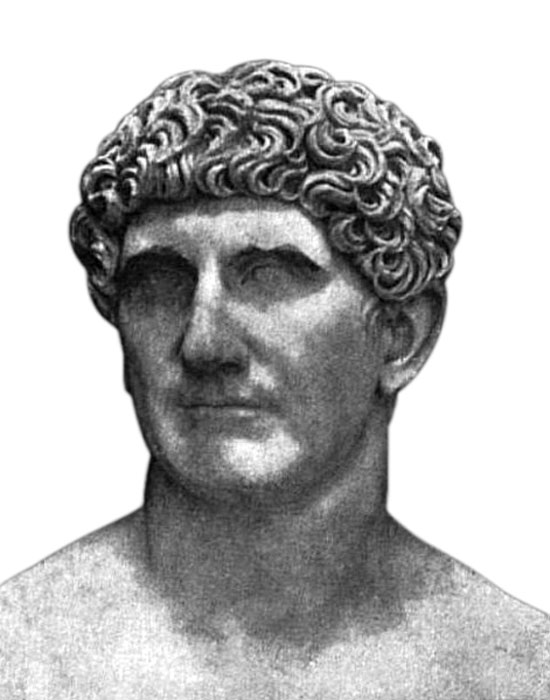

It was the name Mattathiah that got the investigators excited. During the early investigations that were carried out during the 1970s, the ‘Mattathiah’ of the inscription was identified as Antigonus II Mattathias. This was the last king of the Hasmonean Dynasty, the ruling Jewish family that was established following the expulsion of the Seleucids by the Maccabean Revolt. According to the ancient literary sources, Antigonus was captured by the Roman Marc Antony and then executed by crucifixion and beheading.

Early analysis of the ossuary and its contents also led scholars to affirm that this was indeed the final resting place of Antigonus. For example, the ossuary was elaborately decorated and is said to be considered as one of the most beautiful that has ever been found. This could mean that the person interred in this ossuary was someone important, perhaps a king like Antigonus.

In addition, preliminary analysis of the bones indicates that they belonged to a person about 25 years of age, which is consistent with what is known about Antigonus’ age.

Moreover, indications of crucifixion and beheading have been found on the remains. For instance, the hand with embedded nails is proof of the crucifixion, whilst a cut mandible and cuts on the second vertebra are signs of a beheading.

Finally, the ossuary was well-hidden in a niche under the floor of the cave, indicating that the burial was done in secret so as to avoid detection by supporters of the new regime, who were enemies of the Hasmoneans.

A New Interpretation and More Questions

This interpretation has been disputed by later investigations and left more questions unanswered. One of the most notable of these investigations is the bone analysis by Patricia Smith of the Hebrew University.

Smith’s analysis suggested that the ossuary in the Abba Cave was likely to have been intended for two adults, one male, and another possibly an older female. In addition, analysis of the cut mandible suggests that this had belonged to the older female, and could have been cut whilst the victim was moving, or after death.

The nails were also found to have been associated with the fingers, and they did not penetrate the bones, hence discounting the evidence of crucifixion.

Still, the case is not entirely closed, as later researchers have questioned Smith’s findings. For instance, the sex of the individual(s) is still a debated question. As an example, one argument is that a mandible is not enough for the sexing of a skeleton, and only a skull or pelvis is able to do so.

Another analysis found that contrary to Smith’s findings, the nails did indeed penetrate the bones of the hand, thus resurrecting the idea that the individual was crucified. Thus, the mystery of the Abba Cave continues and the identity of the individual(s) interred in the ossuary remains to be ascertained.